Establishing new worldwide standards of care for prostate cancer patients

Our researchers played leading roles in major clinical trials, which improved the treatment of prostate cancer and influenced the way oncologists monitor their patients and use surgery, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy.

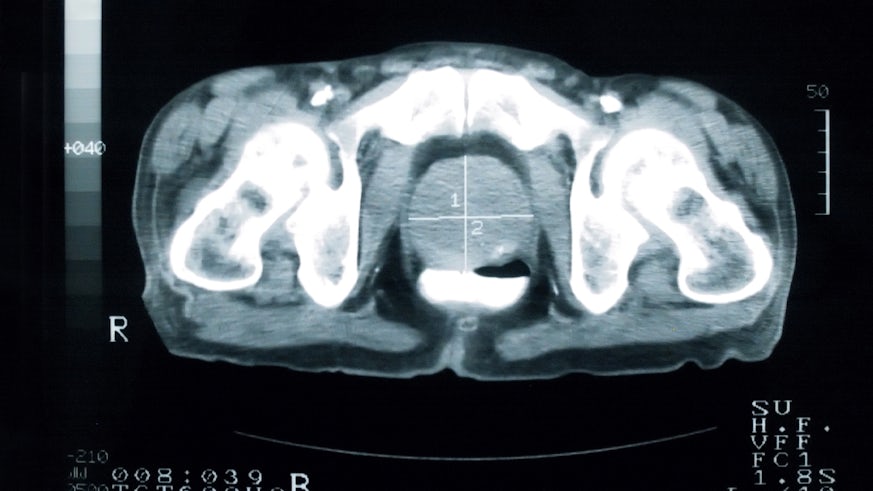

Prostate cancer is the most common male cancer in the United Kingdom.

Previously, some patients received unnecessary treatment that reduced quality of life, while for others, treatment was ineffective.

Early days

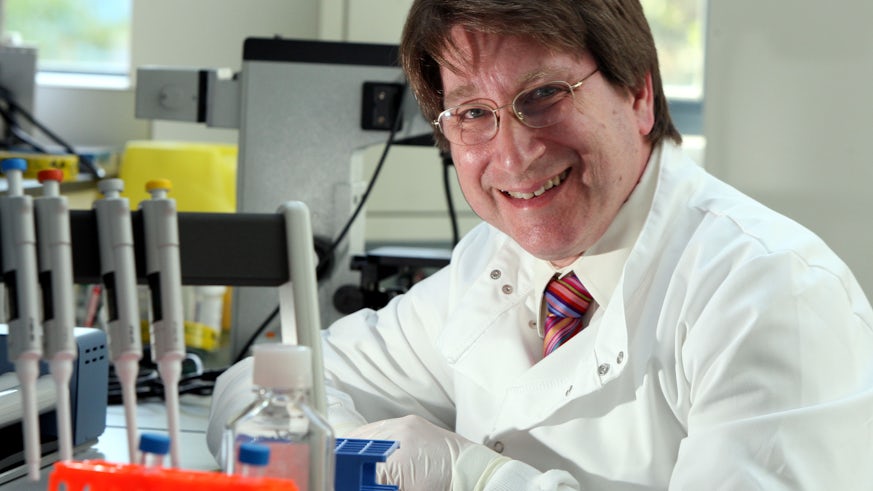

It’s thirty years since Professor Malcolm Mason OBE came to Cardiff to conduct his first clinical trial in prostate cancer.

Professor Mason did his oncology training at the Royal Marsden Hospital in London, where he was mentored by the late Professor Sir Michael Peckham. At the time the unit did research into testicular cancer and lymphomas.

Professor Mason explains, “Professor Sir Michael Peckham made major contributions to research in these areas during my time in training. He retired and his successor, who also became a very good friend, and to whom I owe an enormous amount, was Professor Alan Horwich.

“He expanded the unit to include other urological cancers such as bladder cancer and prostate cancer. When I came back to the unit as a lecturer, there was a very big programme there in prostate cancer research and that sparked my interest.”

The first trial

Professor Mason arrived in Cardiff in 1992, with an idea for a clinical trial in prostate cancer.

This first trial was the start of a career-long relationship with what subsequently became the Medical Research Council (MRC) clinical trials unit.

The trial used a drug called Clodronate, which at the time was the most powerful type of a group of drugs called bisphosphonates. He says, “The idea was to target the bone. Prostate cancer uses the bone’s normal cells to attack and destroy normal bone. Instead of targeting the cancer, this was a strategy targeting the cancer’s target. If it worked, it might have made the bone more resistant to the cancer and might have some benefits for patients.

“We treated over 500 men with prostate cancer, which at the time was one of the biggest prostate cancer studies in the world. We randomly allocated men to have clodronate, or to have a placebo, and then see what happened. When the results were analysed years later, we found – disappointingly – that Clodronate didn’t make any difference at all.

"A newer bisphosphonate agent came along, just a little later, called zoledronic acid, which is much more powerful than the one we had. And that drug was subsequently used in a later clinical trial, called STAMPEDE, to ask the same question again but using a more powerful drug.”

Our understanding and awareness of prostate cancer has changed dramatically since Professor Mason conducted his first clinical trial. Treatments and survival have also changed with thanks, in part to, the subsequent clinical trials that Professor Mason and his colleagues have worked on.

Key studies

MRC PR07 – Locally advanced prostate cancer trial – hormone therapy plus radical radiotherapy versus hormone therapy

This study looked at treatment for locally advanced prostate cancer, which up to that point, had often been treated with hormone therapy alone, the same treatment used for metastatic prostate cancer.

The trial randomly allocated men with locally advanced prostate cancer, to receive standard hormone therapy alone, or to receive radiotherapy as well as hormone therapy. This showed that adding radiotherapy to standard hormone therapy, more than halved the risk of dying for patients with locally advanced prostate cancer.

Over a seven-year period, the number of deaths due to prostate cancer were 9 % for patients receiving radiotherapy and standard hormone therapy, compared to 19 % for patients receiving the standard hormone therapy only.

“I think it was the first time that it was possible to demonstrate, that giving a local treatment to the prostate gland, made a difference to some men and helped them to live longer. That was a real change in our understanding and allowed for a more specific approach to treatment,” Professor Mason explains.

These findings were incorporated into NICE Guidelines, entitled ‘Prostate cancer: diagnosis and management’, first published in 2014 (updated in 2019 and 2021) stating that clinicians should “offer men with intermediate and high-risk localised prostate cancer a combination of radical radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy, rather than radical radiotherapy or androgen deprivation therapy alone.” [new 2014]

STAMPEDE – metastatic prostate cancer trial

For a number of men with prostate cancer, the first symptom they present with is severe pain, typically in the back, but sometimes in other areas. This is due to the cancer having spread, causing metastases to the bones – also known as secondaries – having caused no symptoms at all before doing this.

“STAMPEDE looked at those who presented in this manner as the first time they came to medical attention. They already had widespread disease with secondary tumours, often in the bones, but elsewhere too. We also included those who didn’t have secondaries, but had very, very high risk features in their prostate gland,” Professor Mason says.

Treatment options for advanced stages of prostate cancer were limited and the prognosis was poor. Hormone therapy can produce some dramatic responses, but these are generally temporary. STAMPEDE – a multi-arm, multi-stage trial – tested simultaneously, the effects of adding docetaxel, celecoxib, zoledronic acid, or abiraterone to standard hormone therapy.

Professor Mason explains, “The first thing which appeared to show benefit, was chemotherapy with a drug called docetaxel, which was already being used in men with more advanced disease at the later stage in their disease. It really made a difference there, but, STAMPEDE is showing that you can add other treatments to hormone therapy for patients much earlier in their cancer journey.”

Median survival for the whole group, treated with docetaxel, as well as other drugs such as abiraterone – approximately 4,000 men – was extended from 71 months to 81 months post-diagnosis.

STAMPEDE’s trial results were adopted in clinical practice guidelines in the UK, Europe, and North America. In these parts of the world, the standard of care is no longer conventional hormone therapy alone for patients with advanced prostate cancer.

Two other randomised trials of docetaxel – GETUG 15 and CHAARTED – yielded conflicting results. The STAMPEDE trial convinced the medical community of docetaxel’s benefit due to its significant size, with evidence of an increase in median survival when patients were given docetaxel, in addition to the standard treatment.

ProtecT

“There was a third trial that I was particularly involved in, called ProtecT, which was a trial that looked at the treatment of men who have very, very early stage prostate cancer, because there were enormous questions around the best way of handling this,” Professor Mason says.

ProtecT was the largest global clinical trial for the treatment of localised prostate cancer. Professor Howard Kynaston was the Principal Investigator and lead of the Cardiff ProtecT centre – one of nine in the UK – and Professor Mason designed and led the radiotherapy arm of the trial.

Professor Mason and his colleague, Professor John Staffurth, performed and published the radiotherapy quality assurance. Findings showed that treatment was not always more beneficial than monitoring for localised disease. Where treatment was deemed necessary, radiotherapy had the same effectiveness as surgery.

Results also showed that the risk of dying from prostate cancer is very low – around 1 % – at ten years, irrespective of the treatment, whether this is surgery, radiotherapy, or active monitoring. The risks of disease progression are higher by a small margin with active monitoring, but for most patients, avoiding treatment comes with the benefit of being free from treatment side-effects.

Giving hope to people

Professor Mason says, “Any clinical trial is teamwork. Sometimes I played a leading role in trials, sometimes I’ve played a supportive role, but I’ve had great colleagues throughout. I’ve been lucky enough to be involved with trials which have made several changes in worldwide medical practice.”

“We’re seeing steady improvements in survival in many situations coming out of our trials. It is good to know that things are moving on. I think that gives hope to people who have prostate cancer, and also to specialists working in that area. They know that there are things happening to improve treatment and diagnosis that will help them provide more support to their patients,” he adds.

Cancer research in the School of Medicine

We are driving research for the benefit of patients affected by cancer in Wales and beyond.

Meet the team

Key contacts

Related news

Publications

- Donovan, J. L. et al., 2016. Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 375 , pp.1425-1437. (10.1056/NEJMoa1606221)

- Hamdy, F. et al., 2016. 10-Year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 375 , pp.1415-1424. (10.1056/NEJMoa1606220)

- Dearnaley, D. et al., 2016. Conventional versus hypofractionated high-dose intensity-modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer: 5-year outcomes of the randomised, non-inferiority, phase 3 CHHiP trial. Lancet Oncology 17 (8), pp.1047-1060. (10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30102-4)

- Mason, M. D. et al. 2015. Final report of the intergroup randomized study of combined androgen-deprivation therapy plus radiotherapy versus androgen-deprivation therapy alone in locally advanced prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 33 (19), pp.2143-2150. (10.1200/JCO.2014.57.7510)

- Warde, P. et al., 2011. Combined androgen deprivation therapy and radiation therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: A randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet 378 (9809), pp.2104-2111. (10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61095-7)