Feeding black holes

10 June 2016

Researchers from the School of Physics and Astronomy are amongst the first cohort of international experts ever to witness a supermassive black hole preparing for a "chaotic" feast at the centre of a galaxy.

A group led by Dr Timothy Davis aided the “magical” discovery by preparing and analysing data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA), a telescope based at Chile's Llano de Chajnantor Observatory that is amongst the most powerful in the world.

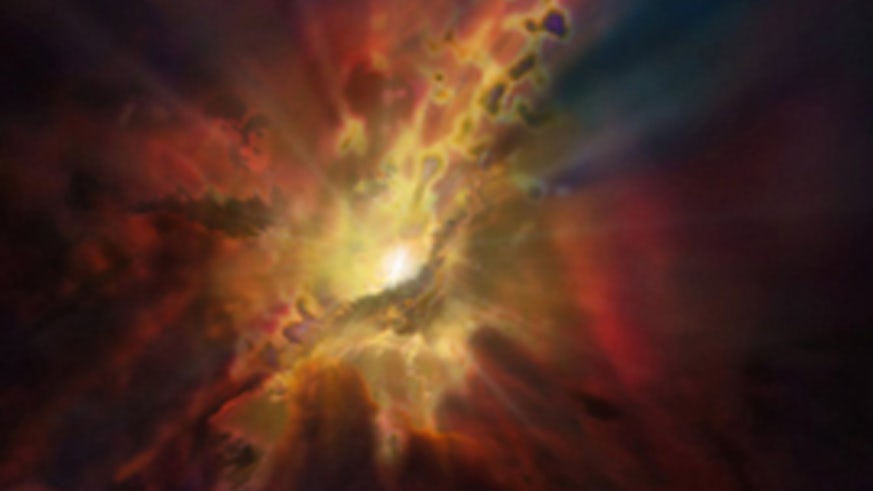

The results, presented on 9th June in Nature journal (Nature 534, 218–221. DOI 10.1038/nature17969), show billowy clouds of cold, clumpy gas streaming towards a supermassive black hole at speeds of up to 800,000 miles per hour and feeding into its bottomless well.

The first direct evidence of the phenomenon was observed in a vast and notably bright galaxy called "Abell 2597", approximately one billion light years from Earth.

“It was magical being able to see evidence of these clouds accreting onto the supermassive black hole,” said the School's Dr Davis. “At that very moment, nature gave us a clear view of this complicated process, allowing us to understand supermassive black holes in a way that has never been possible before."

“The data has provided us with a snapshot of what is happening around the black hole at one precise time, so it iss possible that the black hole has an ever bigger appetite and is devouring even more of these cold clouds of gas surrounding it.”

Previously, it had been hypothesised that the growth – or accretion – of black holes was a smooth process based on the consumption of hot gas, but the involvement of cold gas clouds has shown the growth to be “chaotic” and “clumpy”.

The findings came about after the team attempted to quantify the number of star births in the galaxy, and therefore observed cold gas clouds, the collapse of which provokes star formation.

Instead, they witnessed the shadows of three cold clouds cast against bright jets of material expunged by the black hole, pointing to their imminent absorption.

Professor Michael Macdonald, a co-author based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who worked with the School of Physics & Astronomy, said that the group were “very lucky” to have made the discovery.

“We could probably look at 100 galaxies like this and not see what we saw just by chance. Seeing three shadows at once is like discovering not just one exoplanet, but three in the first try. Nature was very kind in this case.”