Pancreatic cancer - the 'silent killer'

16 March 2017

In a recent article for The Conversation, William Hill, a PhD student at the European Cancer Stem Cell Research Institute, explains why pancreatic cancer would be easier to treat if we could just diagnose it earlier.

Pancreatic cancer wouldn’t be so deadly if we could just diagnose it earlier

Pancreatic cancer is extremely difficult to diagnose. The current prognosis for pancreatic cancer is so poor that a UK cancer charity has warned more than 11,000 people are expected to die from the cancer by 2026, and that it will overtake breast cancer to become the fourth-biggest cancer killer.

Even with current treatments, only 5% of pancreatic cancer patients survive for five years after diagnosis.

The disease has been more in the public conscious recently, following the deaths of Swedish statistician Hans Rosling and British actors John Hurt and Alan Rickman. And though many have quoted the line alongside these reports that survival rates have not improved since the 1960s, for many years scientists have been working on the crucial early diagnosis methods that could save future patients.

Symptoms

Some of the best diagnosed forms of cancer are easily identified with symptoms that everyone is aware of. Melanoma (skin cancer), for example, can be spotted when moles change colour, size and/or shape; 93% of cases are diagnosed in stage one or two because patients can catch it early on themselves. The majority of breast cancer, 83%, is also caught in these early stages as most people have been made aware of the symptoms and know how to check for them.

Unlike breast, skin or one of a number of other easily recognisable cancers, public knowledge of pancreatic cancer symptoms is very low: a recent survey found that more than 70% of people were unable to name a single symptom of the disease unprompted.

However, even if a patient is aware of the symptoms – which include jaundice, abdominal pain, weight loss, changes to appetite and indigestion – they could all easily be attributed to other causes, such as pancreatitis or an ulcer.

On top of this, pancreatic cancer symptoms don’t appear until late on in the disease. It is for these reasons that 80% of pancreatic cancer patients don’t find out they have the disease until it has reached an advanced stage and spread around the body. Once the cancer has begun to spread around the body it makes surgical intervention – the best current treatment – impossible.

Hidden cancer

Detecting pancreatic tumours is not an easy thing to to do, even when symptoms are present. The pancreas is hidden deep in the body, behind the stomach, making it hard for a doctor to feel for tumours during an examination. Its location also creates problems with imaging and taking biopsies when a patient has been referred onwards. Even specialised CT and MRI scans can miss small lesions that indicate the presence of pancreatic cancer.

Blood tests can also be carried out to measure levels of the biomarker – molecules used to identify the disease – carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9). The problem with CA19-9 is that not all pancreatic cancers produce the marker and other diseases can also lead to high levels of the protein.

Quick diagnosis?

We now know that pancreatic cancer takes years to develop into a tumour detectable by current methods. So, potentially, there is a window for diagnoses long before a tumour develops and, with the rise in cases predicted, the need to use this time is urgent.

At present there is no established early detection technique, but moves are being made to improve the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer patients and hopefully catch the illness before it gets too late. Recently a new biomarker was identified that detects pancreatic tumours in blood samples. Following a positive study, this detection technique could be the cheap and sensitive tool for diagnosing the earliest stages of the disease that researchers have been striving for.

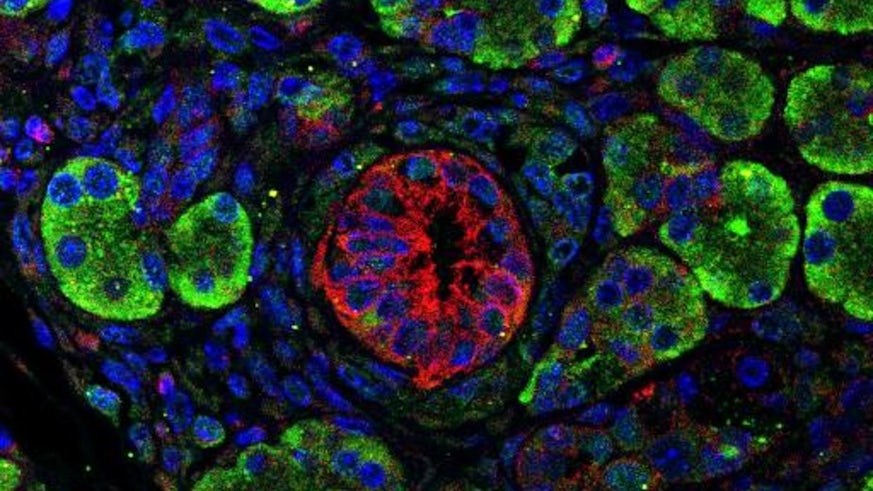

The research investigated the use of extracellular vesicles to detect pancreatic cancer. Extracellular vesicles are tiny membrane-bound packages released by cells. They are secreted into the circulatory system and can be easily found in the blood. Though they were previously dismissed as debris, it is now known that these vesicles carry biomarkers from the cells that produce them.

Using this new detection method the researchers were able to identify early-stage pancreatic cancer in more than 90% of the 59 patients who took part in the pilot study. The technique was even able to distinguish between between cancer and pancreatitis. This proof-of-concept study shows the potential of a non-invasive blood test to detect pancreatic cancer. But more work is required to further validate these findings and to fully automate the test so it can be carried out on a larger scale.

If this test is shown to be accurate in larger trials it could lead to non-invasive large-scale screening for pancreatic cancer. Screening for other types of cancer – such as cervical cancer with smear tests, mammograms for breast cancer, and tests for bowel cancer has revolutionised patient outcome, and this test could very well have the same impact for pancreatic cancer patients.

Though there isn’t an easy way to give a definitive result for pancreatic cancer diagnosis just yet, the work is being done to get there – and tests such as this could potentially save the lives of thousands worldwide.