Breakthrough unravels “big eater” cell

28 April 2014

Studies conducted by a team led by Professor Phil Taylor, and published this week in the prestigious journal Science, shed new light on how the cell type known as macrophages are programmed in tissues.

Macrophages are central to how our body responds to harmful stimuli and tissue injury, including a major role in removing dead cells and foreign material (a literal translation of their name is "big eaters"). Macrophages, and the inflammatory response that they contribute to, can be helpful, for example, killing infecting organisms, or harmful, leading to uncontrolled tissue damage and disability or organ failure. As such, macrophages are important in the maintenance of normal function (termed tissue homeostasis) and in the response to injury of all parts of our body.

Until recently, macrophages were thought to be fairly simple in origin. However, recent studies by Prof. Taylor's group (published in Eur J Immunol 2011 and Nat Commun 2013) and others have shown that there is a lot more complexity to macrophages than this, and have begun to shed light on many different types of macrophage that can be found in normal tissues and in response to injury.

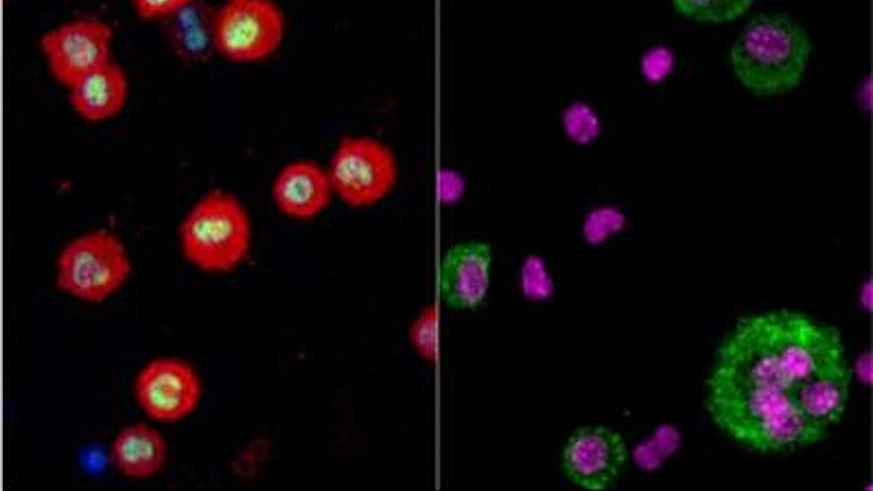

In the paper published this week in Science, Prof. Taylor's group have uncovered how macrophages become specialised for their role in tissue homeostasis in the peritoneal cavity of the abdomen, the site holding the gastrointestinal tract and other abdominal organs. How these cells specialise is key to understanding how they initiate and control inflammation. Having identified a single protein as a master controller of these processes, the scientists can now begin to unlock the secrets that promote healthy tissue function and control inflammation and apply these in a clinical setting.

Specifically, the group used a a 'big-data' approach to understand what genes are turned off and on in different macrophages within a specific tissue and identified a 'master control' of tissue specialisation. After studying the function of this specific master control they concluded that tissue macrophages are programmed in a tissue specific manner that not only controls the type of macrophage they are, but also influences their ability to renew themselves during inflammation. These observations provide significant new insights into what it is to be a tissue macrophage and identify potential new approaches for promoting the return of normal tissue function after inflammation or disease.

The scientists also identified compelling evidence that these processes are relevant in the pleural (chest) cavity, and Prof Taylor states, "this shows that the impact of any such master control could be more broad than initially anticipated, with application in the future treatment of inflammation at other sites. Further studies are now needed to understand the importance of the mechanism that we have uncovered across tissues and diseases".